Next: The Convergence Condition Up: Complex Analysis of Real Previous: An Infinite Collection of

We will now derive certain expressions for the partial sums and for the

corresponding remainders of the Fourier series. In order to do this, let

![]() be a zero-average integrable real function defined on

be a zero-average integrable real function defined on

![]() and let the real numbers

and let the real numbers ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and

![]() , for

, for

![]() , be its Fourier

coefficients. We then define the complex coefficients

, be its Fourier

coefficients. We then define the complex coefficients ![]() and

and

![]() shown in Equation (5), and thus construct the

corresponding proper inner analytic function

shown in Equation (5), and thus construct the

corresponding proper inner analytic function ![]() within the open unit

disk, using the power series

within the open unit

disk, using the power series ![]() given in Equation (6),

which, as was shown in [#!CAoRFI!#], always converges for

given in Equation (6),

which, as was shown in [#!CAoRFI!#], always converges for

![]() . Considering that

. Considering that ![]() , the partial sums of the first

, the partial sums of the first

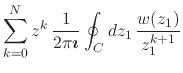

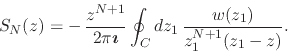

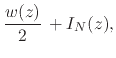

![]() terms of this series are given by

terms of this series are given by

where

![]() , a complex sequence for each value of

, a complex sequence for each value of

![]() which, for

which, for ![]() , we already know to converge to

, we already know to converge to ![]() in the

in the

![]() limit. Note however that, since

limit. Note however that, since ![]() is a polynomial of

order

is a polynomial of

order ![]() and therefore an analytic function over the whole complex plane,

this expression itself can be consistently considered for all finite

and therefore an analytic function over the whole complex plane,

this expression itself can be consistently considered for all finite ![]() and all

and all ![]() , and in particular for

, and in particular for ![]() on the unit circle, where

on the unit circle, where ![]() .

One can also define the corresponding remainders of the complex power

series, in the usual way, as

.

One can also define the corresponding remainders of the complex power

series, in the usual way, as

We will now prove the following theorem.

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

\frac

{

\sin\!\le...

...0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

f(\theta_{1}),$](img209.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

g(\theta_{1}),$](img211.png) |

(53) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

Note that the integral in the expression of the partial sum is the known Dirichlet integral, while the one in the expression of the reminder is similar but not identical to it.

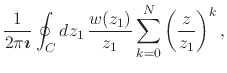

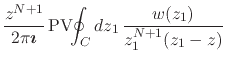

In order to prove this theorem, let us consider the complex partial sums

![]() as given in Equation (51). In addition to this,

the complex coefficients

as given in Equation (51). In addition to this,

the complex coefficients ![]() may be written as integrals involving

may be written as integrals involving

![]() , with the use of the Cauchy integral formulas,

, with the use of the Cauchy integral formulas,

| (54) |

for

![]() , where

, where ![]() can be taken as a circle

centered at the origin, with radius

can be taken as a circle

centered at the origin, with radius ![]() . The reason why we may

include the case

. The reason why we may

include the case ![]() here is that, as was shown in [#!CAoRFI!#], as

a function of

here is that, as was shown in [#!CAoRFI!#], as

a function of ![]() the expression above for

the expression above for ![]() is not only constant

within the open unit disk, but also continuous from within at the unit

circle. In this way the coefficients

is not only constant

within the open unit disk, but also continuous from within at the unit

circle. In this way the coefficients ![]() may be written back in terms

of the inner analytic function

may be written back in terms

of the inner analytic function ![]() . If we substitute this expression

for

. If we substitute this expression

for ![]() back in the partial sums of the complex power series shown in

Equation (51) we get

back in the partial sums of the complex power series shown in

Equation (51) we get

|

|||

|

(55) |

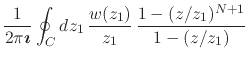

where ![]() can have any value, but where we must have

can have any value, but where we must have ![]() . The

sum is now a finite geometric progression, so that we have its value in

closed form,

. The

sum is now a finite geometric progression, so that we have its value in

closed form,

|

|||

|

(56) |

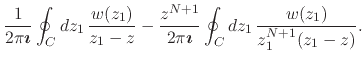

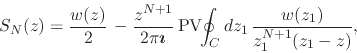

There are now two relevant cases to be considered here, the case in which

![]() and the case in which

and the case in which ![]() . In the first case,

since the explicit simple pole of the integrand at the position

. In the first case,

since the explicit simple pole of the integrand at the position ![]() lies within the integration contour, we have in the first term the Cauchy

integral formula for

lies within the integration contour, we have in the first term the Cauchy

integral formula for ![]() , and therefore we get

, and therefore we get

This is the equation that allows us to write an explicit expression for

the remainder of the complex power series within the open unit disk, thus

making it easier to discuss its convergence there. In the other case, in

which ![]() , the explicit simple pole of the integrand at the

position

, the explicit simple pole of the integrand at the

position ![]() lies outside of the integration contour, and therefore by the

Cauchy-Goursat theorem we just have zero in the first term, so that we get

lies outside of the integration contour, and therefore by the

Cauchy-Goursat theorem we just have zero in the first term, so that we get

|

(58) |

This provides us, therefore, with an explicit expression for the partial

sums, but not for the remainder. The only other possible case is that in

which ![]() , in which both

, in which both ![]() and

and ![]() are over the circle

are over the circle ![]() of radius

of radius ![]() , and therefore so is the explicit simple pole of the

integrand at the position

, and therefore so is the explicit simple pole of the

integrand at the position ![]() . In this case, just as we did before

in Section 3, we may slightly deform the integration contour

. In this case, just as we did before

in Section 3, we may slightly deform the integration contour ![]() in order to have it pass on one side or the other of the simple pole of

the integrand at

in order to have it pass on one side or the other of the simple pole of

the integrand at ![]() . If we use a deformed contour

. If we use a deformed contour ![]() that excludes the pole from its interior, then we have, instead of

Equation (57),

that excludes the pole from its interior, then we have, instead of

Equation (57),

while if we use a deformed contour ![]() that includes the

pole in its interior, then we have, just as in

Equation (57),

that includes the

pole in its interior, then we have, just as in

Equation (57),

Once more, since by the Sokhotskii-Plemelj theorem [#!sokhplem!#] the

Cauchy principal value of the integral over ![]() is the arithmetic average

of these two integrals, taking the average of

Equations (59) and (60) we obtain the

expression

is the arithmetic average

of these two integrals, taking the average of

Equations (59) and (60) we obtain the

expression

|

(61) |

where both ![]() and

and ![]() are now on the circle

are now on the circle ![]() of radius

of radius ![]() .

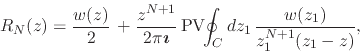

Since we have that the corresponding remainder of the series is defined as

given in Equation (52), we get a corresponding expression

for the remainder, in terms of the same integral,

.

Since we have that the corresponding remainder of the series is defined as

given in Equation (52), we get a corresponding expression

for the remainder, in terms of the same integral,

|

(62) |

where both ![]() and

and ![]() are on the circle

are on the circle ![]() of radius

of radius ![]() . We

have therefore the pair of equations

. We

have therefore the pair of equations

|

|||

|

(63) |

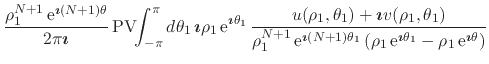

and we must now write the integral ![]() explicitly in terms of

explicitly in terms of

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

|

|||

|

|||

|

(64) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

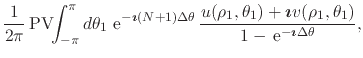

Once again we must rationalize the integrand, and using once more the

result shown in Equation (22) we get

.

Once again we must rationalize the integrand, and using once more the

result shown in Equation (22) we get

|

|||

|

|||

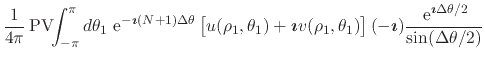

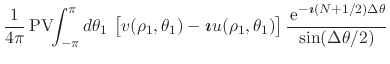

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...ox{\boldmath$\imath$}

\sin(N_{1}\Delta\theta)

\right]

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)},$](img242.png) |

(65) | ||

where

![]() and

and ![]() , with

, with

![]() . Expanding the numerator in the integrand of

this integral we have

. Expanding the numerator in the integrand of

this integral we have

| (66) | |||

and therefore we are left with the following expression for our integral,

|

|||

|

(67) | ||

where

![]() and

and ![]() , with

, with

![]() . Once again we note that, since by

construction the real and imaginary parts

. Once again we note that, since by

construction the real and imaginary parts

![]() and

and

![]() of

of

![]() for

for ![]() are

integrable real functions on the unit circle, and since there are no other

dependencies on

are

integrable real functions on the unit circle, and since there are no other

dependencies on ![]() in this equation, we may now take the

in this equation, we may now take the

![]() limit of this expression, in which the principal

value acquires its usual real meaning on the unit circle, thus obtaining

limit of this expression, in which the principal

value acquires its usual real meaning on the unit circle, thus obtaining

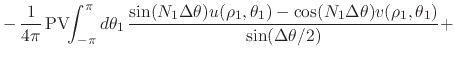

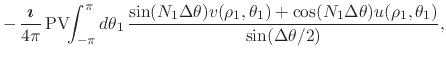

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1...

...{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)}

+$](img250.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int...

...e{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)},$](img251.png) |

(68) | ||

where

![]() and

and

![]() ,

in terms of which we now have the pair of equations at the unit circle

,

in terms of which we now have the pair of equations at the unit circle

|

|||

|

(69) |

Using now the infinite collection of identities in

Equation (50) for the case ![]() , which allow us to

write

, which allow us to

write ![]() in terms of integrals similar to those in

in terms of integrals similar to those in

![]() ,

,

| |||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img260.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{...

...0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

},$](img261.png) |

(70) | ||

where

![]() and

and

![]() ,

we may write for the complex partial sums

,

we may write for the complex partial sums

|

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img260.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img264.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\...

...{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)}

+$](img265.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{...

...e{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)}.$](img266.png) |

(71) | ||

As one can see in this equation, all the terms involving

![]() cancel off, and

therefore we are left with

cancel off, and

therefore we are left with

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img268.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{...

...0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

},$](img269.png) |

(72) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

We now observe that, since by hypothesis

.

We now observe that, since by hypothesis ![]() is integrable on the

unit circle, the Cauchy principal value refers only to the possible

explicit non-integrable singularity of the integrands, due to the zero of

the denominators at

is integrable on the

unit circle, the Cauchy principal value refers only to the possible

explicit non-integrable singularity of the integrands, due to the zero of

the denominators at

![]() . However, since the numerators of

the integrands are also zero at that point, the integrands are not really

divergent at all at that point, so that from this point on we may drop the

principal value. We have therefore our final results for the real partial

sums, for both

. However, since the numerators of

the integrands are also zero at that point, the integrands are not really

divergent at all at that point, so that from this point on we may drop the

principal value. We have therefore our final results for the real partial

sums, for both ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

\frac

{

\sin\!\le...

...m}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

u(1,\theta_{1}),$](img272.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

\frac

{

\sin\!\le...

...m}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

v(1,\theta_{1}),$](img275.png) |

(73) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

These are the well-known results for the partial sums, in terms of

Dirichlet integrals [#!FSchurchill!#]. Note that the two equations above

have exactly the same form, which is to be expected, since the result

holds for all zero-average integrable real functions, including of course

both

.

These are the well-known results for the partial sums, in terms of

Dirichlet integrals [#!FSchurchill!#]. Note that the two equations above

have exactly the same form, which is to be expected, since the result

holds for all zero-average integrable real functions, including of course

both

![]() and

and

![]() . Therefore, given an

arbitrary zero-average integrable real function

. Therefore, given an

arbitrary zero-average integrable real function ![]() on the unit

circle, we have that the partial sums of its Fourier series are given by

on the unit

circle, we have that the partial sums of its Fourier series are given by

![\begin{displaymath}

S_{N}^{F}(\theta)

=

\frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\...

...\rule{0em}{2ex}(\theta_{1}-\theta)/2\right]}\,

f(\theta_{1}),

\end{displaymath}](img276.png) |

(74) |

where

![]() . Note that, although this result is

already very well known, we have showed here that it does follow from our

complex-analytic structure. This completes the proof of the first part of

Theorem 5.

. Note that, although this result is

already very well known, we have showed here that it does follow from our

complex-analytic structure. This completes the proof of the first part of

Theorem 5.

Once more, it is interesting to observe that this relation can be

interpreted as a linear integral operator acting on the space of

zero-average integrable real functions defined on the unit circle, this

time resulting in the ![]() partial sum of the Fourier series of a

zero-average integrable real function, a partial sum which is itself a

zero-average integrable real function. The integration kernel of this

integral operator

partial sum of the Fourier series of a

zero-average integrable real function, a partial sum which is itself a

zero-average integrable real function. The integration kernel of this

integral operator

![]() depends only on

depends only on ![]() and on the

difference

and on the

difference

![]() , and is given by

, and is given by

![\begin{displaymath}

K_{{\cal D}_{\rm s}}(N,\theta-\theta_{1})

=

\frac{1}{2\pi...

...]}

{\sin\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(\theta_{1}-\theta)/2\right]},

\end{displaymath}](img278.png) |

(75) |

where

![]() , so that the action of the operator on

, so that the action of the operator on

![]() can be written as

can be written as

| (76) |

Considering that its kernel is given by a Dirichlet integral, one might

call this the Dirichlet operator, so that the ![]() partial

sum of the Fourier series of

partial

sum of the Fourier series of ![]() is given by the action of this

operator on the zero-average integrable real function

is given by the action of this

operator on the zero-average integrable real function ![]() ,

,

| (77) |

where

![]() . Note that

. Note that

![]() constitutes in fact a whole collection of linear integral operators acting

on the space of zero-average integrable real functions.

constitutes in fact a whole collection of linear integral operators acting

on the space of zero-average integrable real functions.

Using once more the very same elements that were used above for the complex partial sums, we may also write corresponding results for the complex remainders,

|

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img260.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img264.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{1}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1...

...{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)}

+$](img250.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{4\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int...

...e{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{\sin(\Delta\theta/2)}.$](img283.png) |

(78) | ||

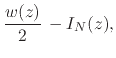

As one can see in this equation, this time all the terms involving

![]() chancel off, and

therefore we are left with

chancel off, and

therefore we are left with

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

v(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}

+$](img285.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{\mbox{\boldmath$\imath$}}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int...

...0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

u(1,\theta_{1})

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

},$](img286.png) |

(79) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

We have therefore our results for the real remainders, for both

.

We have therefore our results for the real remainders, for both

![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...m}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

v(1,\theta_{1}),$](img289.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -\,

\frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1...

...m}{2ex}(N+1/2)\Delta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

u(1,\theta_{1}),$](img292.png) |

(80) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

Recalling that

.

Recalling that

![]() and that

and that

![]() almost everywhere over the unit circle, this completes the proof of

Theorem 5.

almost everywhere over the unit circle, this completes the proof of

Theorem 5.

We believe that these are new results, written in terms of integrals which

are similar to the Dirichlet integrals, but not identical to them. Note

that the remainder of the series of ![]() is given as an integral

involving its Fourier-conjugate function

is given as an integral

involving its Fourier-conjugate function ![]() , and vice versa.

Therefore, we conclude that the convergence condition of the Fourier

series of a given real function does not depend directly on that function,

but only indirectly, through the properties of its Fourier-conjugate real

function.

, and vice versa.

Therefore, we conclude that the convergence condition of the Fourier

series of a given real function does not depend directly on that function,

but only indirectly, through the properties of its Fourier-conjugate real

function.

Since we know that these two real functions are related by the compact Hilbert transform, we may write these equations as

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...ta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

{\cal H}_{\rm c}[u(1,\theta_{1})],$](img293.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta_{1}\,

...

...ta\theta\right]

}

{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

{\cal H}_{\rm c}[v(1,\theta_{1})],$](img294.png) |

(81) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

Note that the two results are now identical in form. Therefore, given an

arbitrary zero-average integrable real function

.

Note that the two results are now identical in form. Therefore, given an

arbitrary zero-average integrable real function ![]() on the unit

circle, we have our final result for the remainder of its Fourier series,

on the unit

circle, we have our final result for the remainder of its Fourier series,

![\begin{displaymath}

R_{N}^{F}(\theta)

=

\frac{1}{2\pi}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\i...

...{

\sin(\Delta\theta/2)

}\,

{\cal H}_{\rm c}[f(\theta_{1})],

\end{displaymath}](img295.png) |

(82) |

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

Once again, it is interesting to observe that this relation can be

interpreted as a linear integral operator acting on the space of

integrable zero-average real functions defined on the unit circle. The

operator

![]() , acting on the compact Hilbert transform

, acting on the compact Hilbert transform

![]() of such a function, results in the

of such a function, results in the ![]() remainder of

the Fourier series of the original function

remainder of

the Fourier series of the original function ![]() , a remainder

which, if it exists at all, is itself a zero-average integrable real

function. The integration kernel of the integral operator depends only on

, a remainder

which, if it exists at all, is itself a zero-average integrable real

function. The integration kernel of the integral operator depends only on

![]() and on the difference

and on the difference

![]() , and is given by

, and is given by

where

![]() , so that the action of the operator on

an arbitrarily given zero-average integrable real function

, so that the action of the operator on

an arbitrarily given zero-average integrable real function ![]() can

be written as

can

be written as

| (84) |

This new operator, which we might refer to as the conjugate Dirichlet

operator, is similar to the Dirichlet operator, and is such that the

![]() remainder of the Fourier series of the real function

remainder of the Fourier series of the real function

![]() is given by the action of this operator on the

Fourier-conjugate function

is given by the action of this operator on the

Fourier-conjugate function ![]() of the real function

of the real function ![]() ,

,

| (85) |

where

![]() . Note once more that

. Note once more that

![]() constitutes in fact a whole collection of linear

integral operators acting on the space of zero-average integrable real

functions. Note also that, since by hypothesis

constitutes in fact a whole collection of linear

integral operators acting on the space of zero-average integrable real

functions. Note also that, since by hypothesis ![]() and

and ![]() are integrable on the unit circle, the Cauchy principal value refers only

to the explicit non-integrable singularity of the integration kernel at

are integrable on the unit circle, the Cauchy principal value refers only

to the explicit non-integrable singularity of the integration kernel at

![]() . In this operator notation we have therefore that the

remainder of the Fourier series of an arbitrarily given zero-average

integrable real function

. In this operator notation we have therefore that the

remainder of the Fourier series of an arbitrarily given zero-average

integrable real function ![]() is given by the composition of

is given by the composition of

![]() with

with

![]() ,

,

| (86) |

Note that, according to the inverse of the relation shown in Equation (42) we may write as well that

| (87) |

which constitutes an equivalent way to express the remainder of the

Fourier series of ![]() in terms of the function itself.

in terms of the function itself.

Finally note that, given the results obtained here for the partial sums and remainders of the Fourier series, the expressions in the infinite collection of identities shown in Equation (50) have now, in fact, the very simple interpretation that was alluded to there, since we now see that they can in fact be written as

| (88) |

where

![]() , a fact which greatly clarifies the

nature of that infinite collections of identities.

, a fact which greatly clarifies the

nature of that infinite collections of identities.