Next: Conclusions and Outlook Up: Complex Analysis of Real Previous: Remainders of Fourier Series

Given an arbitrary zero-average integrable real function ![]() defined on the unit circle, the necessary and sufficient condition for the

convergence of its Fourier series at the point

defined on the unit circle, the necessary and sufficient condition for the

convergence of its Fourier series at the point ![]() is stated very

simply as the condition that

is stated very

simply as the condition that

| (89) |

where

![]() is the remainder of that Fourier series, as

given in Section 6. According to what was shown in that Section,

in terms of the integral operator

is the remainder of that Fourier series, as

given in Section 6. According to what was shown in that Section,

in terms of the integral operator

![]() this translates

therefore as the condition that

this translates

therefore as the condition that

| (90) |

where ![]() is the Fourier-conjugate function of

is the Fourier-conjugate function of ![]() , which

is given by the compact Hilbert transform

, which

is given by the compact Hilbert transform

![]() , leading

therefore to the composition of the two operators,

, leading

therefore to the composition of the two operators,

| (91) |

Equivalently, we may define the linear integral operator

![]() to be this composition of

to be this composition of

![]() with

with

![]() ,

,

| (92) |

that therefore maps ![]() directly onto the

directly onto the ![]() remainder

of its Fourier series,

remainder

of its Fourier series,

| (93) |

so that the convergence condition of the Fourier series of ![]() can

now be written as

can

now be written as

| (94) |

Combining the integration kernels of the operators

![]() ,

given in Equation (83), and

,

given in Equation (83), and

![]() , given in

Equation (27), we may write an integration kernel for the

operator

, given in

Equation (27), we may write an integration kernel for the

operator

![]() , which is not given explicitly, but rather

remains expressed as an integral over the unit circle,

, which is not given explicitly, but rather

remains expressed as an integral over the unit circle,

in terms of which the action of the operator

![]() on

on

![]() is given by

is given by

| (96) |

Note that at this point it is not clear whether or not the integration

kernel depends only on the difference

![]() . We will prove

that it does, and we will also write it in a somewhat more convenient

form. In this section we will prove the following theorem.

. We will prove

that it does, and we will also write it in a somewhat more convenient

form. In this section we will prove the following theorem.

where the integration kernel is given by

Note that the two integrals in this form of the condition are almost

identical, differing only by the exchange of ![]() for

for ![]() . Note also that

the integrands of these integrals are singular at the points

. Note also that

the integrands of these integrals are singular at the points

![]() . Note, finally, that the condition in

Equation (97) means that the remainder

. Note, finally, that the condition in

Equation (97) means that the remainder

![]() must exist, being a finite number for each

must exist, being a finite number for each ![]() , as well as that its

, as well as that its

![]() limit must be zero. The existence of the remainder is, of

course, equivalent to the existence of the integrals involved.

limit must be zero. The existence of the remainder is, of

course, equivalent to the existence of the integrals involved.

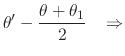

We start by making in the integral in Equation (95) the transformation of variables

|

|||

|

(99) |

which implies that

|

|||

|

(100) |

and which also implies that

![]() , so that we have

, so that we have

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi^{2}}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta''\...

.../4\right]

\sin\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}\theta''/2+(\theta-\theta_{1})/4\right]

},$](img331.png) |

(101) | ||

where ![]() with

with

![]() , and where we do

not have to change the integration limits since the integration runs over

a circle. Note that at this point it is already clearly apparent that

, and where we do

not have to change the integration limits since the integration runs over

a circle. Note that at this point it is already clearly apparent that

![]() depends only on

depends only on ![]() and on the difference

and on the difference

![]() , and therefore from now on we will write it as

, and therefore from now on we will write it as

![]() . Changing

. Changing ![]() back to

back to ![]() and

using the notation

and

using the notation

![]() we have

we have

where

![]() and

and ![]() with

with

![]() . We will now manipulate the denominator

. We will now manipulate the denominator

![]() and the numerator

and the numerator

![]() in this

integrand using trigonometric identities. We start with the denominator,

and using the trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles we get

in this

integrand using trigonometric identities. We start with the denominator,

and using the trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles we get

| (103) |

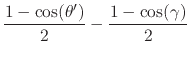

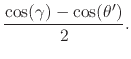

If we now write the cosines in terms of the corresponding sines we have

| (104) |

Using now the half-angle trigonometric identities we finally have

|

|||

|

(105) |

It is important to note that this is an even function of ![]() .

Turning now to the numerator

.

Turning now to the numerator

![]() , and using the

trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles we get

, and using the

trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles we get

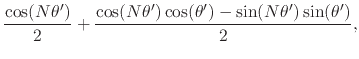

| (106) |

Of these four terms, the first and last ones are even on ![]() , and

the two middle ones are odd. Since the denominator is even and the

integral on

, and

the two middle ones are odd. Since the denominator is even and the

integral on ![]() shown in Equation (102) is over a

symmetric interval, the integrals of the two middle terms will be zero,

and therefore we can ignore these two terms of the numerator. We thus

obtain for our kernel

shown in Equation (102) is over a

symmetric interval, the integrals of the two middle terms will be zero,

and therefore we can ignore these two terms of the numerator. We thus

obtain for our kernel

| (107) |

where the new numerator is given by

![$\displaystyle \left\{

\rule{0em}{2.5ex}

\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\theta'\right]

\cos(\theta'/2)

\right\}

\cos(N_{1}\gamma)

\cos(\gamma/2)

+$](img362.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle -

\left\{

\rule{0em}{2.5ex}

\sin\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\theta'\right]

\sin(\theta'/2)

\right\}

\sin(N_{1}\gamma)

\sin(\gamma/2),$](img363.png) |

(108) |

where

![]() and

and ![]() with

with

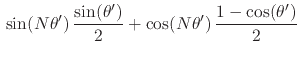

![]() . Using once again the trigonometric

identities for the sum of two angles in order to work on the two

expressions within pairs of curly brackets, we get

. Using once again the trigonometric

identities for the sum of two angles in order to work on the two

expressions within pairs of curly brackets, we get

![$\displaystyle \left\{

\rule{0em}{2.5ex}

\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\theta'\right]

\cos(\theta'/2)

\right\}$](img365.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \left\{

\rule{0em}{2.5ex}

\sin\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1/2)\theta'\right]

\sin(\theta'/2)

\right\}$](img369.png) |

|||

| (109) |

Using now the half-angle trigonometric identities in order to eliminate

the functions

![]() and

and

![]() in favor of

in favor of

![]() and

and ![]() , we get

, we get

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

(110) |

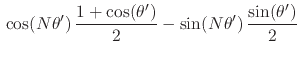

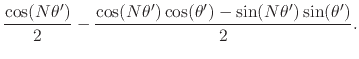

Using once more the trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles we get

![$\displaystyle \frac{\cos(N\theta')}{2}

+

\frac{\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\theta'\right]}{2},$](img380.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{\cos(N\theta')}{2}

-

\frac{\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\theta'\right]}{2}.$](img381.png) |

(111) |

We get therefore for our new numerator, using yet gain the trigonometric identities for the sum of two angles,

![$\displaystyle \frac{\cos(N\theta')}{2}

\left[

\rule{0em}{2ex}

\cos(N_{1}\gamma)

\cos(\gamma/2)

-

\sin(N_{1}\gamma)

\sin(\gamma/2)

\right]

+$](img382.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle +

\frac{\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\theta'\right]}{2}

\left[...

...ex}

\cos(N_{1}\gamma)

\cos(\gamma/2)

+

\sin(N_{1}\gamma)

\sin(\gamma/2)

\right]$](img383.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{\cos(N\theta')\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\gamma\right]}{2}

+

\frac{\cos\!\left[\rule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\theta'\right]\cos(N\gamma)}{2}.$](img384.png) |

(112) |

We therefore have for the kernel

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{4\pi^{2}}\,

\mbox{\rm PV}\!\!\int_{-\pi}^{\pi}d\theta'\,...

...ule{0em}{2ex}(N+1)\theta'\right]\cos(N\gamma)

}

{

\cos(\gamma)-\cos(\theta')

},$](img385.png) |

(113) | ||

where

![]() and

and

![]() .

This is exactly the form of the integration kernel of the operator

.

This is exactly the form of the integration kernel of the operator

![]() given in Equation (98), so that this

completes the proof of Theorem 6.

given in Equation (98), so that this

completes the proof of Theorem 6.

Since the condition stated in Theorem 6 is a necessary and

sufficient condition on the real function ![]() for the convergence

of its Fourier series, any other such condition must be equivalent to it.

Note that this type of condition is not really what is usually meant by a

Fourier theorem. Those are just sufficient conditions for the convergence,

usually related to some fairly simple and easily identifiable

characteristics of the real functions, such as continuity,

differentiability, existence of lateral limits, or limited variation.

However, all such Fourier theorems must be related to this condition in

the sense that they must imply its validity.

for the convergence

of its Fourier series, any other such condition must be equivalent to it.

Note that this type of condition is not really what is usually meant by a

Fourier theorem. Those are just sufficient conditions for the convergence,

usually related to some fairly simple and easily identifiable

characteristics of the real functions, such as continuity,

differentiability, existence of lateral limits, or limited variation.

However, all such Fourier theorems must be related to this condition in

the sense that they must imply its validity.