Next: The Classification Up: Real Functions for Physics Previous: The Low-Pass Filters

In a previously mentioned paper [9] it was shown that the

first-order linear low-pass filter, in its real form, tends to the

identity operator almost everywhere in the ![]() limit. In

Section 6 of Appendix A of that paper one can find a simple proof that in

this limit the filtered function reproduces the value of the original

function whenever that function is continuous, that is

limit. In

Section 6 of Appendix A of that paper one can find a simple proof that in

this limit the filtered function reproduces the value of the original

function whenever that function is continuous, that is

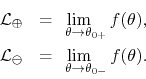

which holds at every point where ![]() is continuous. At isolated

points of discontinuity where the two lateral limits of the original

function to the point of discontinuity exist, the filtered function

converges, in the

is continuous. At isolated

points of discontinuity where the two lateral limits of the original

function to the point of discontinuity exist, the filtered function

converges, in the ![]() limit, to the average of the two lateral

limits, as shown in Section 7 of that same Appendix,

limit, to the average of the two lateral

limits, as shown in Section 7 of that same Appendix,

where

When the two limits coincide, and therefore the original function is

continuous at the point ![]() , this of course reduces to the

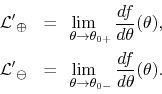

previous property. At isolated points of non-differentiability where the

two lateral limits to that point of the derivative of the original

function exist, the derivative of the filtered function converges, in the

, this of course reduces to the

previous property. At isolated points of non-differentiability where the

two lateral limits to that point of the derivative of the original

function exist, the derivative of the filtered function converges, in the

![]() limit, to the average of these two lateral limits, as

shown in Section 8 of that same Appendix,

limit, to the average of these two lateral limits, as

shown in Section 8 of that same Appendix,

where

Of course, this implies that, at points where the function ![]() is

differentiable, the derivative of the filtered function converges, in the

is

differentiable, the derivative of the filtered function converges, in the

![]() limit, to the derivative of the original function. From

all this we may conclude that, so long as there is only a finite number of

singular points, or at most an infinite but zero-measure set of such

points, in the

limit, to the derivative of the original function. From

all this we may conclude that, so long as there is only a finite number of

singular points, or at most an infinite but zero-measure set of such

points, in the ![]() limit the real filter becomes the identity

operator almost everywhere.

limit the real filter becomes the identity

operator almost everywhere.

In addition to this, one can easily prove that the corresponding complex

filter always becomes exactly the identity operator in the

![]() limit, within the open unit disk. This was commented on

in [3], but since it is quite crucial to our current argument

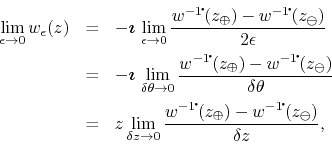

let us repeat the demonstration here. We can see this from the

complex-plane definition in Equation (4). If we consider the

variation of

limit, within the open unit disk. This was commented on

in [3], but since it is quite crucial to our current argument

let us repeat the demonstration here. We can see this from the

complex-plane definition in Equation (4). If we consider the

variation of ![]() between the extremes

between the extremes ![]() and

and ![]() ,

which is given in terms of the parameter

,

which is given in terms of the parameter ![]() by

by

![]() , and we take the

, and we take the ![]() limit of that

expression, we get

limit of that

expression, we get

where we used the fact that in the limit

![]() .

Since we have that

.

Since we have that

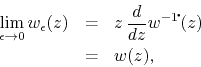

![]() , we see that the

limit above defines the logarithmic derivative of

, we see that the

limit above defines the logarithmic derivative of

![]() . In

addition to this, since that function is analytic in the open unit disk,

the limit necessarily exists. Therefore, we have

. In

addition to this, since that function is analytic in the open unit disk,

the limit necessarily exists. Therefore, we have

since we have here the logarithmic derivative of the logarithmic

primitive, and the operations of logarithmic differentiation and

logarithmic integration are the inverses of one another, as shown

in [2]. We see, therefore, that this property within the open

unit disk is stronger than the corresponding property on the unit circle,

since in this case we have exactly the identity in all cases, while in the

real case we had only the identity almost everywhere. We have therefore

that, for all inner analytic functions ![]() ,

,

which holds in the whole open unit disk. Since every inner analytic

function, filtered or not, corresponds to a real generalized function on

the unit circle in the ![]() limit, defined at all points where this

limit exists, the one-parameter family of inner analytic functions

limit, defined at all points where this

limit exists, the one-parameter family of inner analytic functions

![]() corresponds to a one-parameter family of real

generalized functions

corresponds to a one-parameter family of real

generalized functions

![]() on the unit circle. It is

therefore clear that as

on the unit circle. It is

therefore clear that as

![]() approaches

approaches ![]() in the

in the

![]() limit, so does

limit, so does

![]() approach

approach ![]() in that same limit, at all points of the unit circle where the

in that same limit, at all points of the unit circle where the ![]() limit exists, that is, at least almost everywhere.

limit exists, that is, at least almost everywhere.