Next: Factorization of Singularities Up: Monotonic Series Previous: A Monotonicity Test

The argument given in the last subsection can be generalized in several

ways, and the generalizations constitute proof of the convergence of wider

classes of series of type ![]() . For example, it can be trivially

generalized to series with negative

. For example, it can be trivially

generalized to series with negative ![]() for all

for all ![]() , converging to

zero from below. It is also trivial that it can be generalized to series

which include a non-monotonic initial part, up to some minimum value

, converging to

zero from below. It is also trivial that it can be generalized to series

which include a non-monotonic initial part, up to some minimum value

![]() of

of ![]() . In a less trivial, but still simple way, the argument can

be generalized to series with only odd-

. In a less trivial, but still simple way, the argument can

be generalized to series with only odd-![]() terms, such as the square wave,

or with only even-

terms, such as the square wave,

or with only even-![]() terms, such as the two-cycle sawtooth wave. We can

prove this in a simple way by reducing these cases to the previous one. If

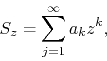

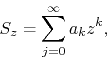

we have a complex power series given by

terms, such as the two-cycle sawtooth wave. We can

prove this in a simple way by reducing these cases to the previous one. If

we have a complex power series given by

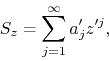

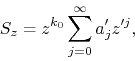

where ![]() , we may simply define new coefficients

, we may simply define new coefficients ![]() and a

new complex variable

and a

new complex variable ![]() , in terms of which the series can now be

written as

, in terms of which the series can now be

written as

thus reducing it to the previous form, in terms of the variable ![]() . So

long as the non-zero coefficients

. So

long as the non-zero coefficients ![]() tend monotonically to zero as

tend monotonically to zero as

![]() , we have that the coefficients

, we have that the coefficients ![]() tend monotonically to

zero as

tend monotonically to

zero as ![]() , and the previous result applies. The same is true if

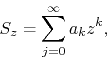

we have a complex power series given by

, and the previous result applies. The same is true if

we have a complex power series given by

where ![]() , since we may still define new coefficients

, since we may still define new coefficients ![]() and the new complex variable

and the new complex variable ![]() , in terms of which the series can

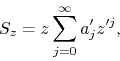

now be written as

, in terms of which the series can

now be written as

so that once more, so long as the non-zero coefficients tend monotonically

to zero, the previous result applies. We say that series such as these

have non-zero coefficients with a constant step ![]() . The only important

difference that comes up here is that the special points on the unit

circle are now defined by

. The only important

difference that comes up here is that the special points on the unit

circle are now defined by ![]() , which means that

, which means that ![]() and hence

that

and hence

that ![]() . Therefore, in these cases one gets two special points on

the unit circle, instead of one, namely

. Therefore, in these cases one gets two special points on

the unit circle, instead of one, namely ![]() and

and ![]() , at

which we have dominant singularities, which will be borderline hard

singularities so long as

, at

which we have dominant singularities, which will be borderline hard

singularities so long as

![]() with

with ![]() .

.

In addition to this, series with step ![]() and coefficients that have

alternating signs, such as

and coefficients that have

alternating signs, such as

![]() with monotonic

with monotonic ![]() ,

which are therefore not monotonic series, can be separated into two

sub-series with step

,

which are therefore not monotonic series, can be separated into two

sub-series with step ![]() , one with odd

, one with odd ![]() and the other with even

and the other with even ![]() ,

and since the coefficients of these two sub-series are monotonic, then the

result holds for each one of the two series, and hence for their sum. In

this case we will have two dominant singularities in each one of the

components series, located at

,

and since the coefficients of these two sub-series are monotonic, then the

result holds for each one of the two series, and hence for their sum. In

this case we will have two dominant singularities in each one of the

components series, located at ![]() . However, sometimes the two

singularities at

. However, sometimes the two

singularities at ![]() , one in each component series, may cancel off and

the original series may have a single dominant singularity located at

, one in each component series, may cancel off and

the original series may have a single dominant singularity located at

![]() . One can see this by means of a simple transformation of variables,

. One can see this by means of a simple transformation of variables,

where ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() implies

implies ![]() . Series with step

. Series with step ![]() and

coefficients that have alternating signs, such as

and

coefficients that have alternating signs, such as

![]() with

with ![]() or

or ![]() and monotonic

and monotonic ![]() , which are also not

monotonic themselves, can be separated into two sub-series with step

, which are also not

monotonic themselves, can be separated into two sub-series with step ![]() ,

and since the coefficients of these two sub-series are monotonic, then the

result holds for each one of the two series, and hence for their sum. In

this case we will have four dominant singularities in each one of the

components series, located at

,

and since the coefficients of these two sub-series are monotonic, then the

result holds for each one of the two series, and hence for their sum. In

this case we will have four dominant singularities in each one of the

components series, located at ![]() and

and

![]() . However, sometimes

the singularities at

. However, sometimes

the singularities at ![]() of the two component series may cancel off

and the original series may have only two dominant singularity located at

of the two component series may cancel off

and the original series may have only two dominant singularity located at

![]() . One can see this by means of another simple transformation of

variables,

. One can see this by means of another simple transformation of

variables,

where ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() implies

implies ![]() and hence

and hence

![]() .

In fact, the result can be generalized to series with non-zero terms only

at some arbitrary regular interval

.

In fact, the result can be generalized to series with non-zero terms only

at some arbitrary regular interval ![]() , that is, having non-zero

terms with some constant step other than

, that is, having non-zero

terms with some constant step other than ![]() . If we have a complex power

series given by

. If we have a complex power

series given by

where ![]() , for some strictly positive integer

, for some strictly positive integer ![]() and where

the step

and where

the step ![]() is another strictly positive integer, we may simply define

new coefficients

is another strictly positive integer, we may simply define

new coefficients ![]() and a new complex variable

and a new complex variable ![]() , in

terms of which the series can now be written as

, in

terms of which the series can now be written as

thus reducing it to the previous form, in terms of the variable ![]() . So

long as the non-zero coefficients

. So

long as the non-zero coefficients ![]() tend monotonically to zero as

tend monotonically to zero as

![]() , we have that the coefficients

, we have that the coefficients ![]() tend monotonically to

zero as

tend monotonically to

zero as ![]() , and the previous result applies. In this case the

special points over the unit circle are given by

, and the previous result applies. In this case the

special points over the unit circle are given by ![]() , and there are,

therefore,

, and there are,

therefore, ![]() such points, including

such points, including ![]() , uniformly distributed along

the circle. If combined with alternating signs, these series have special

points given by

, uniformly distributed along

the circle. If combined with alternating signs, these series have special

points given by ![]() , and once again there are

, and once again there are ![]() such points

uniformly distributed along the circle. Note that the number of dominant

singularities on the unit circle increases with the step

such points

uniformly distributed along the circle. Note that the number of dominant

singularities on the unit circle increases with the step ![]() , and that

they are homogeneously distributed along that circle.

, and that

they are homogeneously distributed along that circle.

Finally, one may consider building finite superpositions of the series in

all the previous cases discussed so far. Since each component series

converges almost everywhere and has a finite number of dominant

singularities, these superpositions of series will all converge, and will

all have a finite number of dominant singularities on the unit disk. Since

all the component series are of type ![]() , and hence have dominant

singularities which are borderline hard ones, the dominant singularities

of the superpositions will always be at most borderline hard ones. If the

dominant singularities are in fact borderline hard ones, then we will call

these series extended monotonic series. Each one of these series

generates a different regular integral-differential chain, and this

defines a rather large set of series that can be classified according to

our scheme, relating their mode of convergence and the dominant

singularities on the unit circle.

, and hence have dominant

singularities which are borderline hard ones, the dominant singularities

of the superpositions will always be at most borderline hard ones. If the

dominant singularities are in fact borderline hard ones, then we will call

these series extended monotonic series. Each one of these series

generates a different regular integral-differential chain, and this

defines a rather large set of series that can be classified according to

our scheme, relating their mode of convergence and the dominant

singularities on the unit circle.