Next: Classification of Singularities Up: Weak Convergence Previous: Weak Convergence

The simplest case of what we call here weak convergence is that in which

there is absolute and uniform convergence at the unit circle to a function

which, although necessarily continuous, is not ![]() . If the

coefficients

. If the

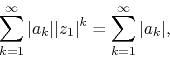

coefficients ![]() are such that the series

are such that the series ![]() is absolutely

convergent on a single point

is absolutely

convergent on a single point ![]() of the unit circle, that is, if the

series of absolute values

of the unit circle, that is, if the

series of absolute values

where ![]() , is convergent, then the series

, is convergent, then the series ![]() is absolutely

convergent on the whole unit circle, given that the criterion of

convergence is clearly independent of

is absolutely

convergent on the whole unit circle, given that the criterion of

convergence is clearly independent of ![]() in this case. For the same

reason, the series in uniformly convergent and thus converges to a

continuous function over the whole unit circle. Therefore the

corresponding FC Fourier series are also absolutely and uniformly

convergent to continuous functions

in this case. For the same

reason, the series in uniformly convergent and thus converges to a

continuous function over the whole unit circle. Therefore the

corresponding FC Fourier series are also absolutely and uniformly

convergent to continuous functions

![]() and

and

![]() over their whole domain.

over their whole domain.

In this case, although the function ![]() must have at least one

singularity on the unit circle, since the series

must have at least one

singularity on the unit circle, since the series ![]() converges

everywhere that function is still well defined over the whole unit circle,

and by Abel's theorem [2] the

converges

everywhere that function is still well defined over the whole unit circle,

and by Abel's theorem [2] the ![]() limit of the

function

limit of the

function ![]() from the interior of the unit disk to the unit circle

exists at all points of that circle. It follows that the singularity or

singularities of

from the interior of the unit disk to the unit circle

exists at all points of that circle. It follows that the singularity or

singularities of ![]() at the unit circle must not involve divergences to

infinity. We will classify such singularities, at which the complex

function is still well-defined, although non-analytic, as soft

singularities. Singularities at which the complex function diverges to

infinity or cannot be defined at all will be called hard

singularities.

at the unit circle must not involve divergences to

infinity. We will classify such singularities, at which the complex

function is still well-defined, although non-analytic, as soft

singularities. Singularities at which the complex function diverges to

infinity or cannot be defined at all will be called hard

singularities.

Since they are convergent everywhere, in this case all DP trigonometric

series are DP Fourier series of the continuous function obtained on the

unit circle by the ![]() limit of the real and imaginary parts of

limit of the real and imaginary parts of

![]() from within the unit disk. In short, we have established that

weakly-convergent FC pairs of DP Fourier series that converge absolutely

and thus uniformly must correspond to inner analytic functions that have

only soft singularities on the unit circle. In fact, this would be true of

any FC pair of DP Fourier series that simply converges weakly everywhere

over the unit circle.

from within the unit disk. In short, we have established that

weakly-convergent FC pairs of DP Fourier series that converge absolutely

and thus uniformly must correspond to inner analytic functions that have

only soft singularities on the unit circle. In fact, this would be true of

any FC pair of DP Fourier series that simply converges weakly everywhere

over the unit circle.

Most of the time this situation can be determined fairly easily in terms

of the coefficients ![]() of the series. If there is a positive real

constant

of the series. If there is a positive real

constant ![]() , a strictly positive number

, a strictly positive number ![]() and an integer

and an integer

![]() such that for

such that for ![]() the absolute values of the coefficients

can be bounded as

the absolute values of the coefficients

can be bounded as

then the asymptotic part of the series of the absolute values of the terms

of ![]() , which is a sum of positive terms and thus increases

monotonically, can be bounded from above by a convergent asymptotic

integral, as shown in Section A.1 of

Appendix A, and thus that series converges. It follows that

the

, which is a sum of positive terms and thus increases

monotonically, can be bounded from above by a convergent asymptotic

integral, as shown in Section A.1 of

Appendix A, and thus that series converges. It follows that

the ![]() series is absolutely and uniformly convergent on the whole

unit circle, and therefore so are the two corresponding DP Fourier series.

series is absolutely and uniformly convergent on the whole

unit circle, and therefore so are the two corresponding DP Fourier series.

If the coefficients tend to zero as a power when ![]() , then it is

easy to see that the limiting function defined by the series cannot be

, then it is

easy to see that the limiting function defined by the series cannot be

![]() . Since every term-wise derivative of the Fourier series with

respect to

. Since every term-wise derivative of the Fourier series with

respect to ![]() adds a factor of

adds a factor of ![]() to the coefficients, a decay to

zero as

to the coefficients, a decay to

zero as

![]() with

with

![]() guarantees that

we may take only up to

guarantees that

we may take only up to ![]() term-by-term derivatives and still end up with

an absolutely and uniformly convergent series. With

term-by-term derivatives and still end up with

an absolutely and uniformly convergent series. With ![]() differentiations

the resulting series might still converge almost everywhere, but that is

not certain, and typically at least one of the two DP series in the FC

pair will diverge somewhere. With

differentiations

the resulting series might still converge almost everywhere, but that is

not certain, and typically at least one of the two DP series in the FC

pair will diverge somewhere. With ![]() differentiations the series

differentiations the series

![]() is sure to diverge everywhere, and the two DP series in the FC

pair are sure to diverge almost everywhere, since the coefficients no

longer go to zero as

is sure to diverge everywhere, and the two DP series in the FC

pair are sure to diverge almost everywhere, since the coefficients no

longer go to zero as ![]() .

.

It is easy to see that the points where one of the limiting functions

![]() and

and

![]() is not differentiable, or

those at which there is a singularity in one of its derivatives, must be

points where

is not differentiable, or

those at which there is a singularity in one of its derivatives, must be

points where ![]() is singular. At any point of the unit circle where

is singular. At any point of the unit circle where

![]() is analytic it not only is continuous but also infinitely

differentiable. We see therefore that the set of points of the unit circle

where

is analytic it not only is continuous but also infinitely

differentiable. We see therefore that the set of points of the unit circle

where

![]() and

and

![]() or their derivatives of

any order have singularities of any kind must be exactly the same set of

points where

or their derivatives of

any order have singularities of any kind must be exactly the same set of

points where ![]() has singularities on that circle. In our present case,

since the functions must be continuous, these singularities can only be

points of non-differentiability of the functions or points where some of

their higher-order derivatives do not exist.

has singularities on that circle. In our present case,

since the functions must be continuous, these singularities can only be

points of non-differentiability of the functions or points where some of

their higher-order derivatives do not exist.

We conclude therefore that the cases in which the convergence is not

strong but is still absolute and uniform are easily characterized. The

really difficult cases regarding convergence are, therefore, those in

which the series are not absolutely or uniformly convergent on the unit

circle. These are cases in which ![]() goes to zero as

goes to zero as ![]() or slower

as

or slower

as ![]() , as shown in Section A.1 of

Appendix A. We will refer to these cases as those of very weak convergence. In this case the Fourier series can converge to

discontinuous functions, and

, as shown in Section A.1 of

Appendix A. We will refer to these cases as those of very weak convergence. In this case the Fourier series can converge to

discontinuous functions, and ![]() will typically diverge at some points

of the unit circle, at which

will typically diverge at some points

of the unit circle, at which ![]() has divergent limits and therefore

hard singularities. In order to discuss this case we must first establish

a few simple preliminary facts, leading to a classification of

singularities according to their severity.

has divergent limits and therefore

hard singularities. In order to discuss this case we must first establish

a few simple preliminary facts, leading to a classification of

singularities according to their severity.