Next: Conclusions and Outlook Up: Complex Analysis of Real Previous: Conformal Transformations and Singularities

The basic idea of the proof of the generalization of the extended

Cauchy-Goursat theorem will be to embed an arbitrarily given integration

contour on the ![]() plane, which must be a simple closed curve but may

or may not be a differentiable curve, into a region bounded by a differentiable simple closed curve, which is then mapped to the unit

circle on the

plane, which must be a simple closed curve but may

or may not be a differentiable curve, into a region bounded by a differentiable simple closed curve, which is then mapped to the unit

circle on the ![]() plane by a conformal transformation. The embedding

will be such that all the isolated integrable singularities on the

original integration contour are mapped onto the unit circle. This will

then allow us to use the extended Cauchy-Goursat theorem for inner

analytic functions within the unit disk, which was established in

Section 3, to prove the generalized version of that theorem.

Therefore, in this section we will prove the following theorem.

plane by a conformal transformation. The embedding

will be such that all the isolated integrable singularities on the

original integration contour are mapped onto the unit circle. This will

then allow us to use the extended Cauchy-Goursat theorem for inner

analytic functions within the unit disk, which was established in

Section 3, to prove the generalized version of that theorem.

Therefore, in this section we will prove the following theorem.

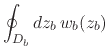

| (24) |

This is the most complete generalization of the extended Cauchy-Goursat theorem that we will consider here, the only relevant limitation being that the number of isolated integrable singularities be finite.

Let ![]() be an analytic function within a closed simple curve

be an analytic function within a closed simple curve

![]() on the

on the ![]() plane, and let the function

plane, and let the function ![]() also be

analytic almost everywhere on

also be

analytic almost everywhere on ![]() , with the exception of a

finite number of isolated integrable singular points. It follows that, due

to Lemmas 1-4, the corresponding function

, with the exception of a

finite number of isolated integrable singular points. It follows that, due

to Lemmas 1-4, the corresponding function

![]() on the

on the ![]() plane will have the same number of

singularities on it, which will also be isolated integrable singular

points. The curve

plane will have the same number of

singularities on it, which will also be isolated integrable singular

points. The curve ![]() may not be differentiable at some points,

including at some of the singular points. We will consider the integral of

may not be differentiable at some points,

including at some of the singular points. We will consider the integral of

![]() over the integration contour

over the integration contour ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane,

which will then, of course, correspond to the integral of

plane,

which will then, of course, correspond to the integral of ![]() over a corresponding integration contour

over a corresponding integration contour ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane,

under the conformal transformation.

plane,

under the conformal transformation.

|

The proof that follows will depend on the integration contour ![]() being either differentiable or non-differentiable and convex at all

the singular points found on it. However, this is not a true limitation,

because an integration contour that has one of more singular points where

it is non-differentiable and concave can always be decomposed into two or

more integration contours where those same singular points are convex, as

is shown in Figure 5 for an example with three such points. As

one can see, all the three integration contours into which the original

one is decomposed by the cuts shown (dashed lines) are convex at the

singular points. When the three are put together to form once again the

original contour, the integrals over those cuts, which due to their

orientation are traversed once in each direction, cancel out. Therefore,

if the theorem is proven for all contours which are convex at the singular

points, it follows that it in fact holds for all contours, regardless of

whether they are convex or concave at their singular points. We may

therefore limit the proof to contours which are convex at all their

singular points.

being either differentiable or non-differentiable and convex at all

the singular points found on it. However, this is not a true limitation,

because an integration contour that has one of more singular points where

it is non-differentiable and concave can always be decomposed into two or

more integration contours where those same singular points are convex, as

is shown in Figure 5 for an example with three such points. As

one can see, all the three integration contours into which the original

one is decomposed by the cuts shown (dashed lines) are convex at the

singular points. When the three are put together to form once again the

original contour, the integrals over those cuts, which due to their

orientation are traversed once in each direction, cancel out. Therefore,

if the theorem is proven for all contours which are convex at the singular

points, it follows that it in fact holds for all contours, regardless of

whether they are convex or concave at their singular points. We may

therefore limit the proof to contours which are convex at all their

singular points.

Given an integration contour ![]() within which

within which ![]() is

analytic, and on which

is

analytic, and on which ![]() is analytic except for a finite

number of isolated integrable singularities, at all of which the contour

is either differentiable or non-differentiable and convex, we consider now

the construction on the

is analytic except for a finite

number of isolated integrable singularities, at all of which the contour

is either differentiable or non-differentiable and convex, we consider now

the construction on the ![]() plane of a new closed differentiable

simple curve

plane of a new closed differentiable

simple curve ![]() that contains

that contains ![]() . At any points on

. At any points on ![]() where

where

![]() is analytic there is a neighborhood of that point within

which there are no singularities of

is analytic there is a neighborhood of that point within

which there are no singularities of ![]() which are not located

directly on

which are not located

directly on ![]() , whose union forms a strip around

, whose union forms a strip around ![]() . In this

case we make

. In this

case we make ![]() go through these neighborhoods in a differentiable

fashion, outside the interior of

go through these neighborhoods in a differentiable

fashion, outside the interior of ![]() , so that we ensure that no

singularities of

, so that we ensure that no

singularities of ![]() get included on

get included on ![]() or in its

interior, other than those on

or in its

interior, other than those on ![]() . This can be done even at

non-singular points where the integration contour

. This can be done even at

non-singular points where the integration contour ![]() is not

differentiable, in which case we make

is not

differentiable, in which case we make ![]() just go around the point of

non-differentiability of

just go around the point of

non-differentiability of ![]() , in a differentiable fashion, as can be

seen illustrated in Figure 6.

, in a differentiable fashion, as can be

seen illustrated in Figure 6.

|

At points of ![]() where

where ![]() has an isolated integrable

singularity, since the singularity is isolated, there is also a

neighborhood of the point within which there are no other

singularities of

has an isolated integrable

singularity, since the singularity is isolated, there is also a

neighborhood of the point within which there are no other

singularities of ![]() , which is part of the aforementioned strip

around

, which is part of the aforementioned strip

around ![]() . In this case we make

. In this case we make ![]() go through this neighborhood,

still keeping to the outer side of

go through this neighborhood,

still keeping to the outer side of ![]() , in such a way that the curve

runs over the singular point in a differentiable way, which is

possible because

, in such a way that the curve

runs over the singular point in a differentiable way, which is

possible because ![]() is convex at that singular point, as is

illustrated by the point

is convex at that singular point, as is

illustrated by the point ![]() in Figure 6. The singular point

is one which the curve

in Figure 6. The singular point

is one which the curve ![]() will therefore share with

will therefore share with ![]() , as is

also illustrated by the point

, as is

also illustrated by the point ![]() in Figure 6. At singular

points where

in Figure 6. At singular

points where ![]() is differentiable we simply make

is differentiable we simply make ![]() tangent to

tangent to

![]() at that point, as is illustrated by the point

at that point, as is illustrated by the point ![]() in

Figure 6.

in

Figure 6.

The result of this process, taken all around ![]() and including all the

isolated integrable singularities found on it, is a differentiable simple

curve

and including all the

isolated integrable singularities found on it, is a differentiable simple

curve ![]() which contains

which contains ![]() and the singularities on it, but that

contains no other singularities of

and the singularities on it, but that

contains no other singularities of ![]() , and which shares with

, and which shares with

![]() all the points where the relevant isolated integrable

singularities of

all the points where the relevant isolated integrable

singularities of ![]() are located. Since by construction

are located. Since by construction ![]() is a differentiable closed simple curve, by the Riemann mapping theorem

there exists a conformal transformation

is a differentiable closed simple curve, by the Riemann mapping theorem

there exists a conformal transformation ![]() that maps it from

the unit circle. Therefore, the inverse conformal transformation

that maps it from

the unit circle. Therefore, the inverse conformal transformation

![]() will map all the isolated integrable singular

points on

will map all the isolated integrable singular

points on ![]() to the unit circle

to the unit circle ![]() .

.

Since the interior of ![]() in mapped by the inverse transformation

in mapped by the inverse transformation

![]() onto the open unit disk, it follows that the

integration contour

onto the open unit disk, it follows that the

integration contour ![]() , which is contained in

, which is contained in ![]() , is mapped by

, is mapped by

![]() onto a closed simple integration contour

onto a closed simple integration contour ![]() contained in the unit disk in the

contained in the unit disk in the ![]() plane, which will not be

differentiable if

plane, which will not be

differentiable if ![]() is not, but which is contained within the closed

unit disk, and that touches the unit circle only at each one of the

isolated integrable singular points of

is not, but which is contained within the closed

unit disk, and that touches the unit circle only at each one of the

isolated integrable singular points of ![]() on

on ![]() that

correspond to the singularities of

that

correspond to the singularities of ![]() on

on ![]() .

.

Observe that, since the curve ![]() does not contain any singularities

of

does not contain any singularities

of ![]() in its strict interior, the interior of the curve

in its strict interior, the interior of the curve

![]() , which is the open unit disk, does not contain any singularities

of

, which is the open unit disk, does not contain any singularities

of ![]() . Therefore, according to the definition given

in [#!CAoRFI!#],

. Therefore, according to the definition given

in [#!CAoRFI!#], ![]() is an inner analytic function. If we now

consider the integral of

is an inner analytic function. If we now

consider the integral of ![]() over

over ![]() , it is a very simple

thing to change the integration variable from

, it is a very simple

thing to change the integration variable from ![]() to

to ![]() ,

,

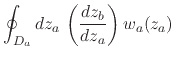

|

|

||

![$\displaystyle \oint_{D_{a}}dz_{a}\,

\left[

\frac{d\gamma(z_{a})}{dz_{a}}

\right]

w_{a}(z_{a}),$](img96.png) |

(25) |

where we used the relations shown in Equations (14)

and (16). Because ![]() is an analytic

function on the whole closed unit disk, the derivative in brackets is also

an analytic function on the whole closed unit disk, and in addition to

this the function

is an analytic

function on the whole closed unit disk, the derivative in brackets is also

an analytic function on the whole closed unit disk, and in addition to

this the function ![]() is analytic within the integration

contour

is analytic within the integration

contour ![]() and also on

and also on ![]() except for a finite set of isolated

singularities located on the unit circle. By the results of

Lemmas 1-4, these isolated singularity are all

integrable ones. Therefore, since the product of two analytic functions is

also an analytic function, the integrand is analytic within the

integration contour

except for a finite set of isolated

singularities located on the unit circle. By the results of

Lemmas 1-4, these isolated singularity are all

integrable ones. Therefore, since the product of two analytic functions is

also an analytic function, the integrand is analytic within the

integration contour ![]() , and also on it except for a finite set of

isolated integrable singularities on the unit circle, and hence is an

inner analytic function. Therefore, by Theorem 1, that is, the

extended Cauchy-Goursat theorem for inner analytic functions on the unit

disk, the integral is zero, and hence it follows that

, and also on it except for a finite set of

isolated integrable singularities on the unit circle, and hence is an

inner analytic function. Therefore, by Theorem 1, that is, the

extended Cauchy-Goursat theorem for inner analytic functions on the unit

disk, the integral is zero, and hence it follows that

| (26) |

In other words, due to the fact that the integral of ![]() on

on

![]() is zero, which is guaranteed by the extended Cauchy-Goursat

theorem for inner analytic functions, we may conclude that the integral of

is zero, which is guaranteed by the extended Cauchy-Goursat

theorem for inner analytic functions, we may conclude that the integral of

![]() on

on ![]() is also zero. This implies that the extended

Cauchy-Goursat theorem is valid for

is also zero. This implies that the extended

Cauchy-Goursat theorem is valid for ![]() , that is, for arbitrary

complex analytic functions anywhere on the complex plane. This completes

the proof of Theorem 2.

, that is, for arbitrary

complex analytic functions anywhere on the complex plane. This completes

the proof of Theorem 2.

Note that, once we have Theorem 2 established, it is also valid for all inner analytic functions, and therefore automatically includes the contents of Theorem 1, which we may therefore regard as just an intermediate step in the proof.