Next: Generalization to Arbitrary Analytic Up: Complex Analysis of Real Previous: Extension of the Cauchy-Goursat

The validity of the extended version of the Cauchy-Goursat theorem can be

generalized to all complex analytic functions integrated on arbitrarily

given closed integration contours, through the use of conformal

transformations. In order to do this, let us first establish the

definition and the notation for a conformal transformation. This is

essentially a shorter version of the discussion on this topic which was

given in Section 4 of a previous paper [#!CAoRFV!#]. Consider therefore

two complex variables ![]() and

and ![]() and the corresponding complex

planes, a complex analytic function

and the corresponding complex

planes, a complex analytic function ![]() defined on the complex

plane

defined on the complex

plane ![]() with values on the complex plane

with values on the complex plane ![]() , and its inverse

function, which is a complex analytic function

, and its inverse

function, which is a complex analytic function

![]() defined

on the complex plane

defined

on the complex plane ![]() with values on the complex plane

with values on the complex plane ![]() ,

,

| (13) |

Let us point out here that these relations immediately imply that

which in turn imply that

| (15) |

for all pairs of points ![]() and

and ![]() related by the conformal

transformation. This means that any point where the derivative of

related by the conformal

transformation. This means that any point where the derivative of

![]() has a zero on the

has a zero on the ![]() plane corresponds to a point

where the derivative of

plane corresponds to a point

where the derivative of

![]() has a singularity on the

has a singularity on the

![]() plane, and vice-versa.

plane, and vice-versa.

Consider a bounded and simply connected open region ![]() on the complex

plane

on the complex

plane ![]() and its image

and its image ![]() under

under ![]() , which is a similar

region on the complex plane

, which is a similar

region on the complex plane ![]() . It can be shown that if

. It can be shown that if ![]() is analytic on

is analytic on ![]() , is invertible there, and its derivative has no

zeros there, then its inverse function

, is invertible there, and its derivative has no

zeros there, then its inverse function

![]() has these same

three properties on

has these same

three properties on ![]() , and the mapping between the two complex

planes established by

, and the mapping between the two complex

planes established by ![]() and

and

![]() is conformal, in

the sense that it preserves the angles between oriented curves at points

where they cross each other. The famous Riemann mapping theorem

states that such a conformal transformation

is conformal, in

the sense that it preserves the angles between oriented curves at points

where they cross each other. The famous Riemann mapping theorem

states that such a conformal transformation ![]() always exists

between the open unit disk

always exists

between the open unit disk ![]() and any region

and any region ![]() . In addition to

this, these properties of

. In addition to

this, these properties of ![]() and

and

![]() can be

extended to the boundary of the regions so long as these boundaries are

differentiable simple curves.

can be

extended to the boundary of the regions so long as these boundaries are

differentiable simple curves.

Consider therefore that the regions under consideration are the interiors

of simple closed curves. One of these curves will be the unit circle

![]() on the complex plane

on the complex plane ![]() , and the other will be a given closed

differentiable simple curve

, and the other will be a given closed

differentiable simple curve ![]() on the complex plane

on the complex plane ![]() . Since

. Since

![]() , being analytic, is in particular a continuous function,

the image on the

, being analytic, is in particular a continuous function,

the image on the ![]() plane of the unit circle

plane of the unit circle ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane must be a continuous closed curve

plane must be a continuous closed curve ![]() . We can also see that

. We can also see that

![]() must be a simple curve, because the fact that

must be a simple curve, because the fact that ![]() is

invertible on

is

invertible on ![]() means that it cannot have the same value at two

different points of

means that it cannot have the same value at two

different points of ![]() , and therefore no two points of

, and therefore no two points of ![]() can be

the same. Consequently, the curve

can be

the same. Consequently, the curve ![]() cannot self-intersect. Finally,

the fact that

cannot self-intersect. Finally,

the fact that ![]() must be a differentiable curve is a simple

consequence of the facts that the

must be a differentiable curve is a simple

consequence of the facts that the ![]() transformation is

conformal and that the unit circle

transformation is

conformal and that the unit circle ![]() is a differentiable curve.

is a differentiable curve.

Given any analytic function ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane, the

conformal transformation

plane, the

conformal transformation ![]() maps it to a corresponding

function

maps it to a corresponding

function ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane, and the inverse conformal

transformation

plane, and the inverse conformal

transformation

![]() maps that function back to the

function

maps that function back to the

function ![]() on the

on the ![]() plane. We can do this by simply

composing either

plane. We can do this by simply

composing either ![]() or

or ![]() with either the

transformation or its inverse, and simply passing the values of the

functions,

with either the

transformation or its inverse, and simply passing the values of the

functions,

Since the composition of two analytic functions is also an analytic

function, and since ![]() is analytic on the closed unit disk,

whenever

is analytic on the closed unit disk,

whenever ![]() is analytic on the

is analytic on the ![]() plane the corresponding

function

plane the corresponding

function ![]() will also be analytic at the corresponding points

on the

will also be analytic at the corresponding points

on the ![]() plane. Of course, where one of these two functions has an

isolated singularity on its plane of definition, so will the other on the

corresponding point in the other plane. Note that if any of these

functions is integrated over a closed integration contour on which it has

any isolated integrable singularities, whenever these singularities are

branch points we assume that the corresponding branch cuts extend outward from the integration contours.

plane. Of course, where one of these two functions has an

isolated singularity on its plane of definition, so will the other on the

corresponding point in the other plane. Note that if any of these

functions is integrated over a closed integration contour on which it has

any isolated integrable singularities, whenever these singularities are

branch points we assume that the corresponding branch cuts extend outward from the integration contours.

The concepts of a soft singularity and of a borderline hard singularity

can be immediately extended from the case of inner analytic functions

within the unit disk to singularities of arbitrary complex analytic

functions anywhere on the complex plane. The concept of a soft singularity

of ![]() at

at ![]() depends only on the existence of the

depends only on the existence of the ![]() limit of

limit of ![]() . The concept of a hard singularity of

. The concept of a hard singularity of ![]() at

at ![]() depends only on the non-existence of that same limit. Finally, the concept

of a borderline hard singularity can be defined as that of a hard

singularity which is nevertheless an integrable one. In order to discuss

what happens with the singularities under the conformal transformation, we

must establish a few simple preliminary results, by means of the following

lemmas.

depends only on the non-existence of that same limit. Finally, the concept

of a borderline hard singularity can be defined as that of a hard

singularity which is nevertheless an integrable one. In order to discuss

what happens with the singularities under the conformal transformation, we

must establish a few simple preliminary results, by means of the following

lemmas.

Since according to Equations (16) we have that

![]() and since

and since

![]() is analytic within and on the image of

the unit circle by the conformal transformation, if

is analytic within and on the image of

the unit circle by the conformal transformation, if ![]() were

analytic at

were

analytic at ![]() , then

, then ![]() would be analytic at

would be analytic at ![]() ,

because the composition of two analytic functions is also an analytic

function. Therefore, if

,

because the composition of two analytic functions is also an analytic

function. Therefore, if ![]() is singular at

is singular at ![]() , then

, then

![]() must be singular at

must be singular at ![]() . This establishes

Lemma 1.

. This establishes

Lemma 1.

Since according to the definition in Equations (16) we

have that

![]() and since the

and since the

![]() limit on the

limit on the ![]() plane corresponds, through the continuous conformal

transformation, to the

plane corresponds, through the continuous conformal

transformation, to the

![]() limit on the

limit on the ![]() plane, it

follows that if the limit

plane, it

follows that if the limit

| (17) |

exists, then so does the limit

| (18) |

Therefore, if the singularity of ![]() at

at ![]() is a soft

one, which means that the first limit exists, then the singularity of

is a soft

one, which means that the first limit exists, then the singularity of

![]() at

at ![]() is also a soft singularity, since in this case

the second limit also exists. This establishes Lemma 2.

is also a soft singularity, since in this case

the second limit also exists. This establishes Lemma 2.

By an argument similar to the one used in Lemma 2, since

according to the definition in Equations (16) we have

that

![]() , and since the

, and since the

![]() and

and

![]() limits correspond to one another, if

limits correspond to one another, if ![]() is

not well defined at

is

not well defined at ![]() , which means that the limit

, which means that the limit

| (19) |

does not exist, then the limit

| (20) |

also does not exist, and therefore ![]() cannot

be well defined at the corresponding point

cannot

be well defined at the corresponding point ![]() . Therefore, if the

singularity of

. Therefore, if the

singularity of ![]() at

at ![]() is a hard one, then the

singularity of

is a hard one, then the

singularity of ![]() at

at ![]() must also be a hard

singularity. This establishes Lemma 3.

must also be a hard

singularity. This establishes Lemma 3.

If the singularity of ![]() at

at ![]() is an integrable one,

then the integral of

is an integrable one,

then the integral of ![]() along any open integration contour

along any open integration contour

![]() going from a point

going from a point ![]() internal to

internal to ![]() to the singular

point

to the singular

point ![]() ,

,

| (21) |

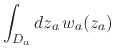

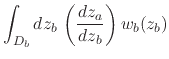

exists and is a finite complex number. We consider now the corresponding

integral of ![]() along an arbitrary open integration contour

along an arbitrary open integration contour

![]() going from an internal point

going from an internal point ![]() within the open unit disk

to the singular point

within the open unit disk

to the singular point ![]() on the unit circle, and make a

transformation of the integration variable from

on the unit circle, and make a

transformation of the integration variable from ![]() to

to ![]() ,

,

|

|

||

![$\displaystyle \int_{D_{b}}dz_{b}\,

\left[

\frac{d\gamma^{(-1)}(z_{b})}{dz_{b}}

\right]

w_{b}(z_{b}),$](img90.png) |

(22) |

where we used the relations shown in Equations (14)

and (16), where ![]() is an open integration contour

going from an internal point

is an open integration contour

going from an internal point ![]() to the singular point

to the singular point ![]() ,

and where

,

and where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() correspond respectively to

correspond respectively to

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , through the conformal transformation.

Since the conformal transformation is an analytic function, the derivative

within brackets is also an analytic function within and on

, through the conformal transformation.

Since the conformal transformation is an analytic function, the derivative

within brackets is also an analytic function within and on ![]() , and

therefore is a limited function there. Since

, and

therefore is a limited function there. Since ![]() by hypothesis

is an integrable function around the singular point

by hypothesis

is an integrable function around the singular point ![]() , and since

the product of a limited function and an integrable function is also an

integrable function, the integrand of this last integral is an integrable

function, and therefore this last integral exists and is a finite complex

number. We thus conclude that

, and since

the product of a limited function and an integrable function is also an

integrable function, the integrand of this last integral is an integrable

function, and therefore this last integral exists and is a finite complex

number. We thus conclude that

| (23) |

exists and is a finite complex number. Therefore, ![]() is an

integrable function around the singular point

is an

integrable function around the singular point ![]() , and therefore

that singularity is also an integrable one. This establishes

Lemma 4.

, and therefore

that singularity is also an integrable one. This establishes

Lemma 4.

We must now consider the question of what is the set of curves ![]() for

which the structure described above can be set up. Given the curve

for

which the structure described above can be set up. Given the curve

![]() , the only additional objects we need in order to do this is the

conformal mapping

, the only additional objects we need in order to do this is the

conformal mapping ![]() and its inverse

and its inverse

![]() ,

between that curve and the unit circle

,

between that curve and the unit circle ![]() , as well as between the

respective interiors. The existence of these transformation functions can

be ensured as a consequence of the Riemann mapping theorem, and of the

associated results relating to conformal mappings between regions of the

complex plane [#!RMPQiu!#]. According to that theorem, a conformal

transformation such as the one we just described exists between any

bounded simply connected open set of the plane and the open unit disk, and

can be extended to the respective boundaries so long as the curve

, as well as between the

respective interiors. The existence of these transformation functions can

be ensured as a consequence of the Riemann mapping theorem, and of the

associated results relating to conformal mappings between regions of the

complex plane [#!RMPQiu!#]. According to that theorem, a conformal

transformation such as the one we just described exists between any

bounded simply connected open set of the plane and the open unit disk, and

can be extended to the respective boundaries so long as the curve ![]() is differentiable. There are therefore no additional limitations on the

differentiable simple closed curves

is differentiable. There are therefore no additional limitations on the

differentiable simple closed curves ![]() that may be considered here.

that may be considered here.